A video by Luksan Wunder, apparently, on how to pronounce German. I’m not sure how the speaker gets through without laughing, but presumably they were done one at a time. Thanks to Jacky, who posted it on the pt list.

Category Archives: Germanlang

Words – Wörter

Asylerheblichkeit

Globuli

phloem

podocarp

fish ladder

‘non-refoulement’

Schrankentrias

Verabschiedungskultur

smile timer

Baumpfleger

Goethe Institut online library

It seems one can hire ebooks and audio and video media online from the Goethe Institut – have not tried it myself.

You may have to search a bit.

Thanks to Cherry for the tip.

The importance of learning German

It seems we in Britain still expect important events to be conducted in English. Thus the experience of the Telegraph’s ‘live blogger’ Ben Bloom yesterday:

Jürgen Klopp to quite Borussia Dortmund on July 1 – as it happened

14.00

And with that I bid you farewell. Again, many apologies for a hopeless lack of German knowledge. You’d think it would have been a prerequisite to live blog a Borussia Dortmund press conference but perhaps not. Only time will tell if the person who tweeted me suggesting I am getting “sacked in the morning” is correct.

I also apologise for this live blog becoming far too much about me. I can assure you it will not happen again. Let us end on what we came here for: Jurgen Klopp. It isn’t often that one of the world’s leading managers becomes available so expect the speculation to run, run and run some more until he gets another job. It’ll be interesting.

Thanks for joining me. Cheerio.

We like Jürgen Klopp and second that. And doubt whether it was his fault that he was given an assignment he could not understand.

15.20

Sadly, Ben Bloom has now gone home to start his German lessons. But he appears to have become something of a web sensation in the meantime, so here are some of the funniest tweets about his ridiculous press conference coverage.

(PS. We haven’t fired him. Yet.)

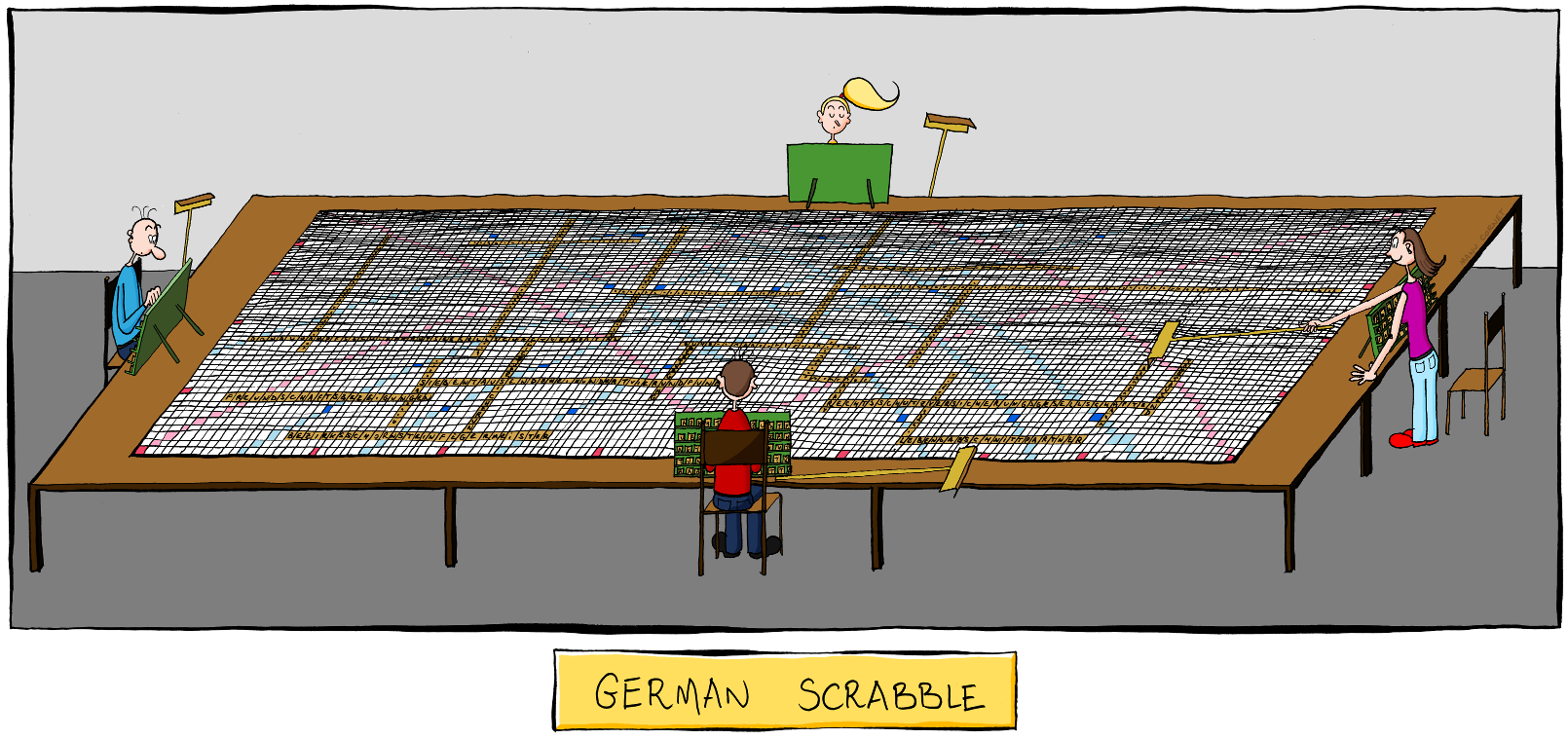

German Scrabble

This cartoon is by Emmanuel Cornet, whose interesting bio can be found on his website. It shows that nowadays you don’t have to remain a French maths teacher, or even a bass and guitar player, all your life. I found the cartoon at www.bonkersworld.net.

Thanks to Herb for the tip.

Changing terminology

In another mailing list last week, I was struck by the question of how to translate the term divorce decree into German.

One would normally write Scheidungsurteil, but recently the term Urteil has been removed from German divorce law, apparently because it makes divorce sound like a fight (haha!). Indeed, all family law cases now end in a Beschluss, which sounds more harmless, allegedly.

See Es gibt keine Scheidungsurteile mehr in Thomas von der Wehl’s blog.

Wir haben nur durch das neue FamFG eine neue Begrifflichkeit erhalten. Aus einem schwer nachvollziehbaren Grunde hat der Gesetzgeber den Begriff Scheidungsurteil abgeschafft und durch den Begriff Scheidungsbeschluss ersetzt. Er wollte damit ausdrücken, dass es sich bei Scheidungsverfahren um angeblich weniger streitige Verfahren handelt und dieses Weniger an Streit mit dem etwas geringerwertigen Begriff “Beschluss” kenntlich machen. Ich halte das für Unsinn, zumal die Vermutung, Scheidungsverfahren seien weniger weniger streitige Verfahren, häufig falsch ist.

So the colleague’s question was: do we change the translated term to suit new German practice? The answer on all sides was ‘no’.

And yet when English law removed the term plaintiff and replaced it by claimant, translators in the UK followed suit, even though the term plaintiff is used in Ireland and thus in the EU, and also in the USA and other common-law jurisdictions. And similarly, in family law, it’s common to use contact instead of access in translations, just because the term has changed in English law.

Of course one has to consider how close the concepts are in German law and English law. And also whether the audience is from one specific jurisdiction – it’s statistically more sensible to use plaintiff unless the readership are purely from the UK.

I’m trying to think of other cases where changes in terminology might affect translations. One area is the introduction of ‘politically correct’ usage, which may occur in the USA and UK before it does in Germany. Should a German institution use non-sexist language in its English documentation even if it doesn’t in German? I think so.

The names of courts, court personnel and lawyers often change. So do forms of companies and partnerships.

Of course, many concepts are not close and the target language needs a definition. It’s only terms like Scheidungsurteil and plaintiff that are close enough that one wonders whether to follow changes in the target language.