At the moment I am being targeted by comment spammers. They have only spammed the older entries, where comments have to be approved. None of their comments has any relevance to the post and they all link to different websites, which I’m not convinced are really websites. All the addresses are @smr.edu.pl, but the beginning of the address varies. Does this mean they are not actually from Poland? I have a feeling there is no point in writing to the Polish webmaster to complain. I just have to keep deleting them.

E.J. Cohn Manual of German Law

I know it’s Sunday, but I’d like to plug a law book. Before I came to Germany, when I was first encountering German law, I picked up two volumes of this at Wildy’s , 2nd edition, 1968 and 1971, for £5 and £6, which was a bargain at the time (about 1980).

E.J. Cohn was a German who was a barrister of Lincoln’s Inn. His book goes through the German Civil Code of the time, explaining it in English for English lawyers. There is a German index as well as an English one, and in the first volume a copy from the German Land Register (Grundbuch) and a bibliography. The second volume deals with commercial law, but also conflict of laws, civil procedure, banktuptcy, nationality and family law of East Germany. I must admit I’ve mainly used the first book. But now looking at the page describing the Prokurist and the beginning of nationality (the law of nationality has changed somewhat now), both compared with the situation in England and Wales in a clear way, I can confirm that the book is still useful today – not as a guide to current German law, but as a comparative introduction to German law, which it places in its historical context.

Unfortunately I haven’t found extracts online. There are articles about the book, but none accessible without payment. Here’s the abstract of an article about German lawyers uprooted:

Ernst Joseph Cohn was born in Breslau, Germany on August 7, 1904 to Max Cohn and Charlotte Ruß. Before taking up his studies at the law faculty of the University of Leipzig in Germany, he attended the primary and secondary schools of his home town. His doctoral thesis deals with problems of communication of declarations of intention through the medium of messengers, in particular with the legal effect of a declaration received by a messenger. He obtained his doctorate degree as a summa cum laude. This chapter chronicles Cohn’s legal education and academic career in Germany, his legal research and publications before leaving Germany and emigrating to England, his research on English law as well as international law and comparative law, his interest in civil procedure and arbitration, and his views on private international law and unification of law.

However, you can get the book second-hand online. A search at abebooks.de or abebooks.com will produce some copies. If you leave out the author’s name, you will also find an earlier Foreign Office Manual of German Law (1952) which was written by Cohn.

Note also the latter’s page on bookshop cats.

Here’s a brief extract (section 80 of Volume 1), which I hope shows what a good writer Cohn was:

The importance of legal writings by private writers is far greater in the law of the Federal Republic of Germany than it is in the common law countries. Such writings may be freely quoted in a court of law. Writers of repute enjoy a considerable persuasive authority. If the majority of writers have agreed on a certain view and a dominant view (herrschende Meinung) has thus been formed, the weight of this view in legal practice is great. As judgments of the courts have no binding effect, an attorney who can rely on the dominant opinion as expressed by the standard textbooks and commentaries will be entitled to feel confidence in his case, even though there may be one or two published judgments of inferior courts. Judgments of the courts at all levels often contain references to private writings and sometimes an extensive discussion of the points made by them, in particular where the court wishes to deviate from the views adopted by the writers. References to legal literature will be found throughout this book, although for reasons of space these have been kept to a minimum.

Swimming in Germany/Altdeutsch-Rücken

At last I have discovered what these people who annoy me at the swimming baths are doing. It’s an old-fashioned German swimming stroke. The person swims backwards, moving both arms up, back and forward again simultaneously, in a crablike manner, and taking up an inordinate space in the pool – almost as bad as two women chatting to each other.

The clue was given by a commenter to an entry (in German) by Kaltmamsell. Kaltmamsell swims a lot and I have often envied her fitness and indeed youth, not that I could swim that far when I was younger. She wrote this entry on the problem of large numbers of people in the Olympiabad in Munich. In the smaller pools I go to, it is not so much the young swimmers but the old who cause problems. I also notice at water gymnastics that nearly all old Germans, including the men, make a big point of keeping their hair dry. I can’t help thinking that swimming with your neck bent could lead to vertebra problems, but maybe the sport makes up for that.

I found the above illustration in German Wikipedia:

Altdeutsch-Rücken (oft nur Altdeutsch oder auch Deutscher Kraul sowie Rücken-Gleitzug) ist ein Schwimmstil in Rückenlage. Dabei wird auf dem Rücken die Brustbeinschlagbewegung (Grätschschwung) in Kombination mit einem rückenkraulähnlichen Armzug, bei dem jedoch beide Arme zeitgleich bewegt werden, ausgeführt. Das heißt, sowohl Arme als auch Beine werden jeweils simultan und in jedem Moment symmetrisch zur Körperlängsachse bewegt.

It says one advantage of this stroke is that you can see where you’re going – if you bend your neck far enough.

I have also seen a kind of backwards swimming without arm movements, which I believe is supposed to be good for your back, though I don’t know why.

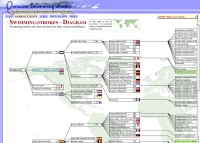

I found a Dutch site, Overview swimming strokes, with English, which shows 150 swimming strokes, with diagrams and animations. Here is a screenshot of part of their big diagram:

I can’t work out which the German backstroke is – it might be the ‘backstroke of Löwenstrom’.

Another peculiarity is that most people swim breaststroke with their heads out of the water. It seems that this is what is taught at school. I started with crawl. Here is some discussion between English-speaking parents in Germany on the topic at Toytown Germany.

So here’s me picturing my kids back in Oz in a few years time —- bobbing up and down in the sea doing breaststroke with their heads above water, getting absolutely nowhere as their cousins have tears streaming down their faces from laughing so hard! (“Don’t worry about us in out in the surf Mum – we learnt this breast-stroke thing in Germany! See we’re not even getting our faces wet!” … and out to sea they drift!)

Hedy Lamarr/9. November

I’m not sure how many Germans think of November 9 as Tag der Erfinder – Inventors’ Day. After all, we are mainly commemorating the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 or else Kristallnacht in 1938. But I learn from Stephen Albainy-Jenei at Patent Baristas (via Blawg Review) that this was Hedy Lamarr’s birthday, and she is certainly worth an entry.

I learn from the internet that Inventors’ Day was thought up by Ronald Reagan, that the date in German-speaking countries is November 9 (Hedy Lamarr’s birthday), and that the German end is supported by one Gerhard Muthenthaler (Tag der Erfinder website, German).

So this is a day for patent bloggers.

In any case, I am surprised I have never mentioned Hedy (Hedwig) Lamarr, but here is Stephen’s account:

This week we honor Inventors’ Day (German: Tag der Erfinder), which is celebrated in the German-speaking countries Germany, Austria and Switzerland on November 9, the birthday of inventor and Hollywood actress Hedy Lamarr. Lamarr, born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler, was an Austrian-born American actress.

Though known primarily for her film career as a major contract star of MGM’s “Golden Age”, she also co-invented an early technique for frequency-hopped spread spectrum communications in 1942, a key to many forms of wireless communication.

She also escaped from Austria and her controlling husband in 1937 in dramatic circumstances and was married several times more after that.

Thanks to Ed., of course.

The book you want to read next/Das Buch, das du als nächstes lesen willst

I have a couple of boxes full of books that I once wanted to read next, but the one I actually intend to read next is Heimsuchung, by Jenny Erpenbeck, which has just come out in an English translation, Visitation. It’s the story of a house near Berlin and twelve successive inhabitants through the political vicissitudes of German history. It is said to take a while to get into (see the German description by Isabel Bogdan) – it does start off 24,000 years earlier when the ice finishes shaping the landscape.

I was alerted to the book not by the review by Michel Faber in the Guardian (which seems to suggest we should not be reading Jonathan Franzen), but from Katy Derbyshire’s weblog love german books (whose RSS feed never works, so I have to go to the site every few days). Katy writes in English and mainly about books already translated into English, and she always gives me the feeling of telling it like it is, as in the latest entry on the reading at Soho House in Berlin from the original and Susan Bernofsky’s translation.

The book came out in paperback in February 2010, and German books take ages to come out in paperback, so it’s not surprising I couldn’t find it in the small bookshops in Fürth at the weekend, but I did order it at Genniges for Monday. What I wonder is whether I would have found it at Hugendubel in Nuremberg, or even Thalia.

The book you are reading now/Das Buch, das du zurzeit liest

I just got a Sony eReader, of which perhaps more anon, and I decided to read Ulysses in full. We always had that book at home but I could not get far with it, although I liked the beginning. Maybe it was when we were shown extracts from Finnegans Wake in the sixth form that I felt Joyce was not for me. I think we ‘did’ Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man at university (I studied German with subsidiary English).

So on the Reader I have a Penguin copy of the Odyssey, and lying around an old library copy of Harry Blamires guide to Ulysses, The Bloomsday Book – A guide through Joyce’s Ulysses (there is a newer one, but AFAIK it just adapts the page numbers to a newer edition). I bought it through abebooks. It was originally much consulted at West Sussex County Library. It is an unpretentious guide. In the Odyssey, I’ve just got to the point where Odysseus arrives back in Ithaca. The Penguin edition – an E.V.Rieu translation edited by his son – has a very useful chronological summary of the events in it. The Odyssey is anything but chronological in sequence.

I also have and am reading Richard David Precht, Wer bin ich – und wenn ja, wie viele? . This book is a bestseller in Germany. Precht studied philosophy and he set out to explain it to his stepchildren. His approach is unusual. He describes what fun it was to study philosophy and discuss it with other students, and how dry the lectures were, based on a historical approach. I think the title is a quote from a fellow student who was drunk.

An English edition is to be published in April 2011. Here is a page about selling the rights. Here’s the British publisher’s blurb:

There are many books about philosophy, but “Who Am I? And If So How Many?” is different from the rest. Never before has anyone introduced readers so expertly and, at the same time, so light-heartedly and elegantly to the big philosophical questions. Drawing on neuroscience, psychology, history, and even pop culture, Richard David Precht deftly elucidates the questions at the heart of human existence: What is truth? Does life have meaning? Why should I be good? And presents them in concise, witty, and engaging prose. The result is an exhilarating journey through the history of philosophy and a lucid introduction to current research on the brain. “Who Am I? And If So, How Many?” is a wonderfully accessible introduction to philosophy. The book is a kaleidoscope of philosophical problems, anecdotal information, neurological and biological science, and psychological research. The books is divided into three parts: What Can I Know? focuses on the brain and the nature and scope of human knowledge, starting with questions posed by Kant, Descartes, Nietzsche, Freud, and others; What Should I Do? deals with human morals and ethics, using neurological and sociological research to explain why we empathize with others and are compelled to act morally, and discusses the morality of euthanasia, abortion, cloning, and other controversial topics; and, What Can I Hope For? centers around the most important questions in life: What is happiness and why do we fall in love? Is there a God and how can we prove God’s existence? What is freedom? What is the purpose of life?

The final book I am reading is Defending the Guilty, by Alex McBride. This is an inside life of the criminal bar, both prosecuting and defending. You can look inside it at amazon – I have an amazon.de link in the right-hand sidebar. McBride is not like Ferdinand von Schirach – he doesn’t try to keep himself out of the stories. He alternates between stories of courtroom successes and failures and becoming a criminal barrister and brief considerations of problems in criminal law. Thus he starts on a lighthearted note (insofar as chopping up the body of a rabbi and getting the refuse collection day wrong is amusing) before turning to the problems of making a mistake in cross-examination which lets in precisely the evidence which will convict your client. Some of the successful trials are the result of luck.